American Airlines Is Betting on the Wrong Satellite Horse

Imagine a library located 22,000 miles away from your home. Every time you need to read a page, a drone must fly to space and back. This, in effect, is how Viasat delivers internet to passengers aboard American Airlines. While this technological feat once inspired admiration, today it invites concern. American Airlines’ continued reliance on Viasat's geostationary satellites is not merely suboptimal, it is indefensible given the alternatives. Most notably, Starlink has emerged as a superior system, both technologically and operationally. Long-suffering American Airlines passengers deserve better. They deserve Starlink. Viasat's internet service is a legacy product rooted in outdated physics, and American Airlines should halt its rollout and pivot to Starlink if it wishes to deliver on the promise of reliable, free in-flight Wi-Fi.

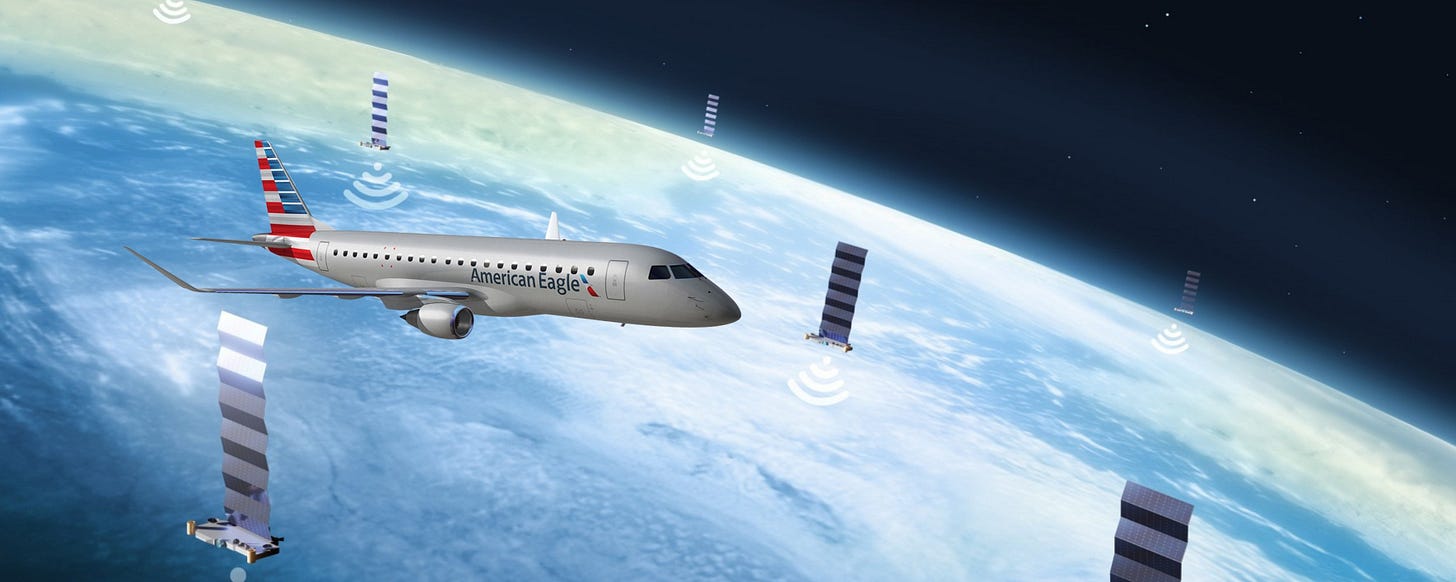

Let us begin by examining the basic geometry of the problem. Viasat's internet infrastructure is based on geostationary satellites, which maintain their orbit 22,236 miles above the Earth's surface. Because of this altitude, signals must traverse an immense distance twice, up to the satellite and then back down to Earth, before data can be received. This physical constraint imposes latency that cannot be engineered away. Average round-trip latency for Viasat is 600 to 800 milliseconds. For a modern internet user accustomed to sub-50 millisecond latency, this creates a perceptible lag that renders video calls choppy, live gaming impossible, and even web browsing sluggish. By contrast, Starlink operates a constellation of low Earth orbit satellites at roughly 300 miles altitude. The difference is not trivial. It is structural. Starlink routinely achieves latencies of 20 to 40 milliseconds, rivaling terrestrial broadband.

To be clear, Viasat is not unaware of its disadvantage. Its ViaSat-3 satellites, recently launched and partially operational, were intended to deliver over one terabit per second of throughput. Yet this figure is now tragically misleading. The first of the ViaSat-3 constellation, launched in 2023, suffered a critical antenna deployment failure that slashed its capacity to less than 10% of its intended throughput. This catastrophic shortfall means that the bandwidth available must not only be divided across an enormous geographic footprint but also begins from a drastically reduced baseline. Real-world performance for a single airplane remains constrained. Testing on American Airlines aircraft shows download speeds around 25 Mbps, and upload speeds from around 10 Mbps. These are barely passable for checking email, but insufficient when scaled to an entire cabin of users, particularly under a free Wi-Fi model. Starlink's performance is significantly better by every measure. In multiple operational scenarios, including United Airlines' early deployments and testing on JSX and Hawaiian Airlines, Starlink terminals have demonstrated per-plane bandwidth exceeding 200 Mbps download and 30 Mbps upload. This is not theoretical. These are operational benchmarks from commercial fleets.

The fragility of Viasat’s system becomes clear when one considers usage dynamics. At present, fewer than 10 percent of passengers on American Airlines flights use Viasat’s paid Wi-Fi. Even with this limited load, passenger complaints about reliability and speed abound. This is not anecdotal; it is systemic. In fact, American is moving to the free Wi-Fi model in large part because it receives so many complaints from paying users. Internally, the hope is that if Wi-Fi is offered at no cost, customers will be less inclined to complain. That premise is flawed. Over time, half of all Viasat users on American flights have requested refunds due to performance issues, creating an immense customer service burden. When American launches free Wi-Fi for AAdvantage members in 2026, usage rates could plausibly rise to 75 percent or more. This will not be a minor increase. It will be a geometric escalation in network demand, driven by video streaming, social media, cloud access, and video conferencing. Viasat’s system, already strained at minimal adoption, cannot scale to meet this demand. Starlink, by contrast, is designed for such scalability. Its high satellite density and mesh network architecture allow it to dynamically allocate bandwidth, prioritizing moving targets like aircraft with minimal latency and high throughput.

One might argue that Viasat’s technology is reliable, tested, and globally available. And in a literal sense, this is true. But reliability, when tethered to underperformance, becomes a liability, not an asset. Starlink has already exceeded 7,000 operational satellites, with over 1,200 launched in 2025 alone. This rate of expansion and replenishment ensures resilience, coverage, and technological refresh at a cadence that Viasat’s aging fleet cannot match. Viasat currently operates four primary GEO satellites, with an average age exceeding a decade. Its two newest satellites were delayed indefinitely due to manufacturing and launch setbacks. This gap is not just logistical; it is existential. Viasat's architecture is inherently static, while Starlink's is iterative and responsive.

Furthermore, Starlink's network is future-proofed in a way that Viasat's cannot be. Elon Musk's team deploys new satellite batches weekly, each incorporating improved hardware and firmware. Meanwhile, a geostationary satellite, once launched, remains technologically fixed for over a decade. The disparity in innovation velocity should give pause to any airline betting on long-term competitiveness.

Consider now the economics. American Airlines has committed substantial capital to retrofitting its fleet with Viasat terminals, often replacing legacy Gogo systems. This retrofit reportedly costs hundreds of thousands of dollars per plane. The instinct to complete what one has begun is understandable, but it is often irrational. Economists call it the sunk cost fallacy. Past investments should not justify continued spending if superior alternatives now exist. Starlink’s installation costs, at approximately $150,000 per plane, are not prohibitive relative to the cost of failure. If free Wi-Fi becomes the new baseline across commercial aviation, as it increasingly is, then customer satisfaction will hinge on performance. A poor internet experience is not a minor annoyance; it is a reputational risk. The difference between buffering and streaming is the difference between repeat business and defection.

A brief analogy may help crystallize the situation. Imagine two bridges. One is made of reinforced steel and spans the river directly. The other is an old wooden ferry system that slowly hauls cars across by rope. The ferry was once a marvel, but now it is an obstruction. Viasat is the ferry. Starlink is the bridge. American Airlines is choosing to upgrade the ferry rather than build the bridge. The error is not merely aesthetic. It is structural. It is operational. It is commercial.

What of the tests that American Airlines cites to defend Viasat? The company claims that Viasat has "exceeded expectations" during initial rollouts of free Wi-Fi. But expectations are relative. These tests were likely conducted under controlled conditions with limited users. They tell us little about real-world performance at scale. The problem with high-latency, low-bandwidth systems is not that they always fail. It is that they cannot be trusted to succeed when demand spikes. When the cabin fills and everyone logs on, the system buckles.

Some readers may reasonably wonder: is the transition to Starlink truly feasible midstream? The answer is yes, and precedents abound. United Airlines has committed to outfitting more than 1,000 aircraft with Starlink by 2028, rolling out 40 planes per month starting in 2025. JSX and Hawaiian Airlines have likewise demonstrated rapid integration. Moreover, American has chosen Intelsat for its regional jets, evidencing flexibility in vendor relationships. The company is not wedded to Viasat. It is simply resistant to course correction.

One final point warrants emphasis: the market is watching. Viasat's hold on approximately 3,750 commercial aircraft is already eroding. United’s switch to Starlink represents a loss of up to $80 million annually for Viasat. If American Airlines persists in its loyalty to an underperforming provider, it risks becoming the last adopter of a vanishing standard. Customers notice. Reviews circulate. Comparisons are inevitable. The airline that cannot deliver basic internet functionality at cruising altitude will suffer in a market where connectivity is no longer a perk but a baseline expectation.

In summary, Viasat’s geostationary satellite service, once an achievement, is now a bottleneck. Its latency is immovable, its bandwidth is inadequate, its fleet is aging, and its innovation is slow. American Airlines is gambling that incremental improvements and legacy loyalty will suffice in an age of exponential expectations. They will not. Starlink offers a faster, more reliable, and future-proof alternative. The prudent course is clear. Halt the rollout. Reallocate resources. Install the bridge, and let the ferry retire.

If you enjoy my work, please consider subscribing https://x.com/amuse.