American Professor Faces 15 Years for Academic Speech Critical of Thailand's King

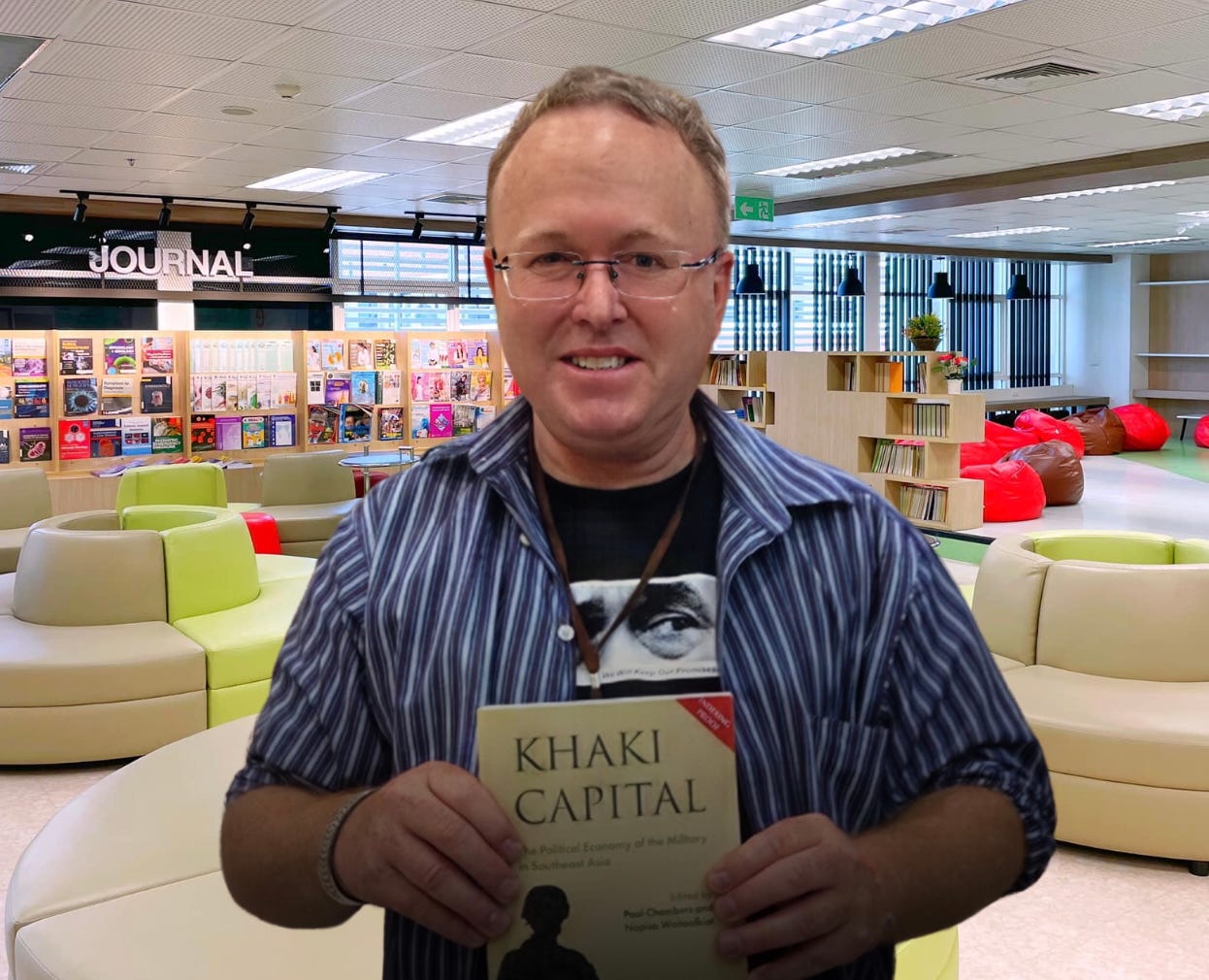

Dr. Paul Chambers is not a revolutionary. He is a scholar, a 58-year-old American academic who has spent more than three decades in Thailand, building a career rooted in analysis, not agitation. Since 1993, Chambers has lectured in political science at Naresuan University, a mid-sized institution in the ancient capital of Phitsanulok, where he also serves as a special adviser at the university's Center for ASEAN Community Studies. He is widely recognized as one of the foremost foreign experts on Thai civil-military relations—a topic that, in the West, might bore the bureaucrats and animate the think tanks, but in Thailand, is politically radioactive.

The state has now decided to treat his scholarship as sedition.

In early April 2025, Thai authorities issued an arrest warrant for Dr. Chambers on charges that carry staggering weight: violating the country’s notorious lèse-majesté statute—Section 112 of the Thai Criminal Code—for allegedly insulting the monarchy during a livestreamed academic webinar. Each utterance that offends the crown may warrant up to 15 years in prison. Because Chambers spoke via an online forum, he is also charged under the Computer Crimes Act, which tacks on an additional five-year sentence for digital dissemination.

If convicted on all counts, Chambers could face decades behind bars. His offense? Discussing the entanglement of military power with monarchical authority—an open secret in Thai politics, yet one that may not be named.

Thailand is no stranger to prosecuting its own citizens under Section 112. Since 2020, at least 278 individuals have faced such charges, often for social media posts, street protests, or academic critiques. What makes Chambers’ case unique—indeed, unprecedented—is that he is not Thai. To anyone’s knowledge, no American has ever been charged, much less arrested, under this law. Chambers himself reflected on the irony with a calm that belied the gravity: "I believe I’m the first non-Thai in years to face this charge."

One might have expected Naresuan University, like many risk-averse institutions, to distance itself from the controversy. Instead, it responded with quiet defiance. When police arrived with the warrant, the university president, Suwat Sutcharit, intervened personally, negotiating a compromise: Chambers would not be arrested publicly in front of students. He would voluntarily report to authorities at a later date. This small act of dignity mattered.

Colleagues have rallied behind him. So too has the U.S. Embassy in Bangkok, which is providing consular support. But support is not salvation, and Chambers has expressed feelings of intimidation, even fear, as he prepares to face a legal machine designed not to investigate truth but to enforce reverence.

What, precisely, is the Thai state protecting? The lèse-majesté statute purports to shield the monarchy from defamation. In practice, it functions as an ideological bludgeon, wielded against critics and scholars alike. Section 112 is not a law; it is a liturgy—a catechism of political sanctity from which deviation is heresy. Dr. Chambers’ crime was not what he said, but that he presumed to say it.

Human rights organizations have responded with predictable outrage, though one suspects the Thai authorities anticipated as much and simply did not care. Sunai Phasuk, senior researcher for Human Rights Watch in Thailand, monitored the case closely, praising the decision not to detain Chambers immediately, while condemning the charges themselves. Phil Robertson, HRW’s Deputy Director for Asia, minced no words: “An astonishing and outrageous assault on academic freedom that will have a serious chilling effect on international studies in Thailand.”

The irony, of course, is painful. Thailand aspires to be a regional hub for higher education, inviting foreign scholars to study, lecture, and publish on Southeast Asian affairs. Yet what international academic—tenured or otherwise—will feel safe analyzing Thai politics now? Who among them will parse royalist-military dynamics, knowing that a seminar might end in shackles?

This is not mere speculation. Thai scholars themselves are watching with alarm. Section 112 has already been weaponized against native academics—those who write about republicanism, democratic reform, or history without the requisite hagiography. But this case represents something new: an escalation, a line crossed. If a respected foreigner can be hauled in under royal defamation laws, then the boundaries of permissible inquiry have all but disappeared.

Opposition voices within Thailand have begun to speak up. Chetawan Tueprakhon, an MP from the reformist Prachachart Party, raised a poignant challenge on social media: “Are we really in a democratic government?... Is the military truly under civilian control?” His question was more than rhetorical. Just days prior to Chambers’ arrest, Thailand’s civilian leaders had shared pleasantries with Myanmar’s junta. Now they silence their own lecturers. To call this governance democratic is to drain the word of all meaning.

There is, moreover, a broader geopolitical hypocrisy at play. Thailand currently holds a seat on the United Nations Human Rights Council, a position presumably premised on some commitment to international norms. And yet, the prosecution of Dr. Chambers places the kingdom squarely in opposition to basic freedoms enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—freedom of opinion, freedom of expression, freedom of academic inquiry.

Foreign media have covered the case with appropriate astonishment. Reuters and AFP reported swiftly, highlighting both the severity of the charges and the rarity of their target. Matichon and Bangkok Post picked up the story domestically, but not without caution—lest reporting itself be construed as disrespectful. This too is a symptom of the rot: a nation where the press must parse its adjectives lest it offend the invisible thresholds of reverence.

The question now is whether the United States will intervene meaningfully. Thus far, statements have been diplomatic. But diplomacy, while necessary, is insufficient. We call on Secretary of State Marco Rubio to condemn these charges unequivocally. We urge Ambassador Robert F. Godec to make it clear that the imprisonment of an American citizen for academic speech is unacceptable. The Department of State must be reminded that its duty is not merely to observe but to defend its nationals—especially those engaged in the peaceful pursuit of knowledge.

None of this is to deny the complexity of Thai politics. The monarchy remains an institution of profound symbolic value to many Thais. But a symbol, however sacred, cannot become a shield for autocracy. In a genuine democracy, even the revered must endure scrutiny. Scholarship without risk is not scholarship—it is ceremony. And if Thailand wishes to join the ranks of mature liberal democracies, it must tolerate, even welcome, the uncomfortable work of intellectual examination.

Dr. Paul Chambers is not a threat to the Thai monarchy. He is a mirror—one that reflects the contradictions and anxieties of a nation still struggling to reconcile tradition with openness. Shattering that mirror will not resolve the tension. It will only signal to the world that Thailand prefers flattery to truth.

And that, not the words of an aging professor on a Zoom call, is the real insult to the monarchy.

If you don't already please follow @amuse on 𝕏.

A phone call from President Trump, commander-in-chief, to the leader of Thailand, should go like this: “imprison or unfairly punish this American, and I will instruct our Military to begin packing our bags. Your Military can deal with China, correct,? Otherwise, apologize to the American and all will be well. Thanks much.“

Why would anyone think that there would be no consequences for critiquing an authoritarian monarch or dictator while within their jurisdiction? One cannot even do that in the YooKay or the EYoo these days.