Canada’s Darkest Secret: The Plan to Strike First Against the US—and Its Modern Echoes

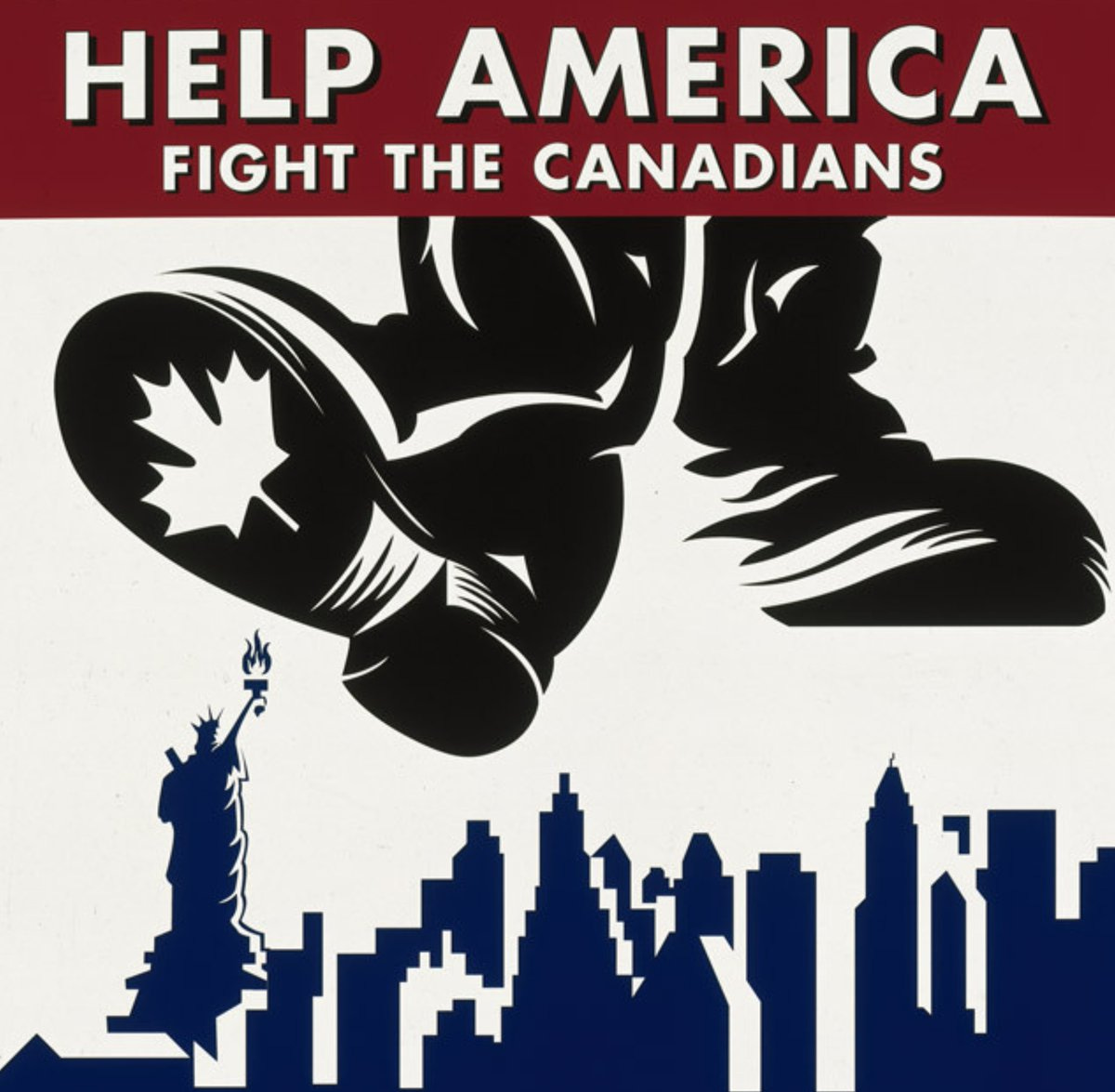

Canada is widely regarded as America’s affable neighbor, a northern bastion of polite society and peaceful coexistence. Its national mythos, carefully curated and exported abroad, paints a picture of unwavering pacifism, an ethos starkly opposed to the supposed aggressiveness of the United States. But history, as it often does, complicates this narrative. In the wake of Donald Trump’s offhand remark calling Justin Trudeau a mere “governor” and suggesting Canada might as well become America’s fifty-first state, some in Canada have indignantly suggested that the true aggressor in North American relations has always been the United States. But this presumption overlooks an inconvenient truth: Canada itself once devised a covert plan to preemptively invade the United States.

In 1921, at a time when Anglo-American relations were far from assured, Canadian military planners crafted Defence Scheme No. 1, a secret war plan to strike first against the United States in the event of war. This was not a mere defensive blueprint; it was an audacious offensive designed to disrupt American mobilization by seizing U.S. territory before an inevitable counterattack. It was, in the most literal sense, a plan of aggression—executed not by the United States, but by the so-called peaceful dominion to its north.

This historical episode throws a glaring light on the ironies embedded in the current diplomatic row between Trump and Trudeau. Canada, often posturing as the innocent party in U.S.-Canadian relations, has its own history of viewing America as a potential adversary. And while Trudeau decries Trump’s dismissiveness as evidence of American arrogance, one wonders whether his own political grandstanding obscures an inconvenient historical reality: Canada has not always been the tranquil pacifist it pretends to be.

The early twentieth century was a period of geopolitical uncertainty. The British Empire still loomed large, and Canada, despite its growing autonomy, was inextricably linked to British foreign policy. The United States, having emerged victorious from the First World War, was asserting itself as the dominant power in the Western Hemisphere. Though relations between the two nations were cordial on the surface, unresolved tensions and a history of conflict—the War of 1812, border disputes, and lingering Anglo-American mistrust—lingered in the background.

In this climate, Canadian military planners, led by Lt. Col. James “Buster” Sutherland Brown, drafted a bold contingency plan: in the event of impending war, Canada would launch a preemptive strike deep into American territory. The plan’s objectives were clear: seize key American cities along the border, disrupt U.S. supply lines, and force Washington to fight on home soil, thus buying time for British reinforcements to arrive. Canadian forces were to push into Washington state, North Dakota, and New York, using surprise and rapid movement to destabilize American defenses before retreating and sabotaging key infrastructure.

At its core, Defence Scheme No. 1 was an admission of Canada’s strategic weakness. Canadian planners understood that in an outright conflict with the United States, they would be overwhelmed. The population disparity alone made long-term resistance untenable. The hope was that by taking the fight to American soil first, Canada could disrupt U.S. war plans enough to delay an inevitable American counteroffensive. In theory, this would provide Britain—Canada’s ultimate protector—sufficient time to intervene.

The irony of this plan is striking in the context of modern political discourse. The idea of American aggression towards Canada is a popular rhetorical device in Canadian politics, a way of reinforcing national identity in opposition to the United States. But Defence Scheme No. 1 makes it clear that such fears were not one-sided. Canada itself once considered the United States a serious enough threat that it saw value in launching an invasion before American forces could react. This was not an act of self-defense, but a calculated effort to neutralize a perceived American threat before it materialized.

Moreover, this historical reality makes Trudeau’s indignation over Trump’s remarks all the more ironic. While Trump’s suggestion that Canada should become America’s fifty-first state is obviously unserious bluster, Trudeau’s wounded response plays into a long-standing Canadian political tradition of casting the United States as the overbearing bully and Canada as the virtuous underdog. But history complicates this narrative. When given the opportunity, Canada’s own military strategists saw no issue with striking first against their larger neighbor.

It is also worth noting that while Canada eventually abandoned Defence Scheme No. 1, the United States developed its own war plan—War Plan Red—which envisioned a swift invasion of Canada in the event of a war with the British Empire. This mirrored the Canadian approach, with U.S. forces aiming to seize key Canadian ports, railways, and industrial centers to prevent a prolonged conflict. These plans, though never acted upon, highlight the mutual suspicion that once defined North American military strategy—a suspicion that Canadians today are quick to attribute solely to the United States, despite their own history of military contingency planning.

The contemporary relevance of this history extends beyond mere irony. The broader lesson of Defence Scheme No. 1 is that national self-interest, not moral purity, drives foreign policy. Nations do not remain peaceful out of principle, but out of necessity. Canada, like any other country, has at times considered aggressive action when it seemed strategically advantageous. Today, Canada enjoys a position of relative security under the U.S. defense umbrella, allowing it to indulge in rhetorical critiques of American militarism while benefitting from the protection of the very power it once feared enough to plan an invasion against.

This is not to say that Canada and the United States are on the brink of conflict today. Far from it. But the notion that Canada is a purely pacifist nation and the United States is the perennial aggressor is a narrative that does not hold up under historical scrutiny. And while Trudeau may protest Trump’s remarks as evidence of American condescension, he would do well to remember that Canada itself has not always been content to simply exist in America’s shadow. History is a stubborn thing, and it does not always conform to the political narratives we would like to impose upon it.

If you don't already please follow @amuse on 𝕏 and subscribe to the Deep Dive podcast.

You are a connoisseur of history! I have no idea why I never heard about this before. I love history of all kinds yet never once was this even alluded to. Great stuff, thank you.