Dilbert’s Creator, Scott Adams, Dead at 68, A Useful Life...

Scott Adams, seen in a familiar midlife frame, a half-smile, a gaze that suggested he was already turning your sentence into a punchline, died on January 13, 2026, at 68, after a battle with metastatic prostate cancer. His former wife, Shelly Miles, announced his death in a live-streamed statement, and in a gesture that was unmistakably Adams, she did not offer a press release or a managed narrative. She read his own words. He had spent his public life insisting that communication matters more than choreography, that clarity matters more than approval, and that the most durable legacy is usefulness. His parting message, which follows later in this obituary, ends with a request that is as simple as it is demanding: be useful.

To read an obituary for a cartoonist is, in one sense, to do something small, to note the dates, to note the work, to offer a brief gratitude, and to move on. But Scott Adams was never simply a cartoonist, and Dilbert was never simply a comic strip. He was a cultural engineer who found the hidden structure of a modern life, the life of smart people trapped inside systems designed by committees, and he translated that structure into a daily language of shared recognition. He also became, later, a polarizing public figure, a man who turned his attentions from corporate nonsense to national politics, media, persuasion, and the civil religion of free speech. Some readers embraced him, some left him, many argued about him, but few who paid attention doubted his influence. If a life can be measured by the number of people who feel less alone because of your work, Adams’s life measures large.

He was born Scott Raymond Adams on June 8, 1957, in Windham, New York, a small Catskills town where winter is long and modesty is not optional. His father was a postal clerk, his mother a real estate agent who later worked on a factory assembly line. The family’s circumstances were ordinary in the best American sense, not glamorous, not tragic, just the sturdy middle ground in which ambition must be self-generated. Adams was bright, and he was funny early, and he learned the crucial lesson that humor is not only entertainment, it is a tool for survival and a tool for truth. In high school he became valedictorian, and later he joked about it the way he joked about everything, deflating the pomp by noting how small the class was, as if to say, yes, I did well, but let’s not pretend it was destiny.

He studied economics at Hartwick College in Oneonta, New York, graduating in 1979. He later pursued an MBA at the University of California, Berkeley, completing it in 1986, and in that arc you can already see the Adams pattern: a pragmatic mind, an appetite for systems, and a willingness to work hard at the unglamorous thing so that the glamorous thing might someday become possible. The story he told again and again was that he loved cartoons as a kid, but he did not begin as an artist in the romantic sense. He began as an American employee.

His early jobs are not footnotes, they are the seedbed. After college he worked as a bank teller at Crocker National Bank in San Francisco, and he was robbed at gunpoint, twice. It is hard to imagine a more compressed tutorial in human incentives. You can read about crime in a paper, but there is a different knowledge that comes from seeing a person’s hand on a weapon and realizing that institutions are often thinner than we like to believe. In later years, when Adams wrote about persuasion, fear, and risk, you could hear the voice of someone who had learned those categories not only as abstractions.

He then joined Pacific Bell, known as PacBell, where he worked as a technologist and later a financial analyst. The culture of corporate bureaucracy became his daily atmosphere. Meetings were not primarily for decisions, they were for signaling. Performance was not primarily for outcomes, it was for optics. Adams would later describe that a large portion of his job involved trying to look busy. It was a sentence that landed because it was true, and it was true in more offices than any one person had the courage to admit.

In that environment, Dilbert was born, not as a grand plan but as a survival tactic. In the late 1980s, Adams began doodling during meetings and on his cubicle whiteboard. The nameless office worker with the curlicue tie and the potato-shaped head was a visual joke at first, but the deeper joke was structural. Dilbert did not exist to ridicule work. Dilbert existed to reveal how power operates when the system is too complex for accountability and too comfortable for reform. In 1989, the strip debuted in syndication. In 1995, as its success became undeniable, he left his day job. In 1997, he won the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year, an honor that placed him in the lineage of America’s great comic artists.

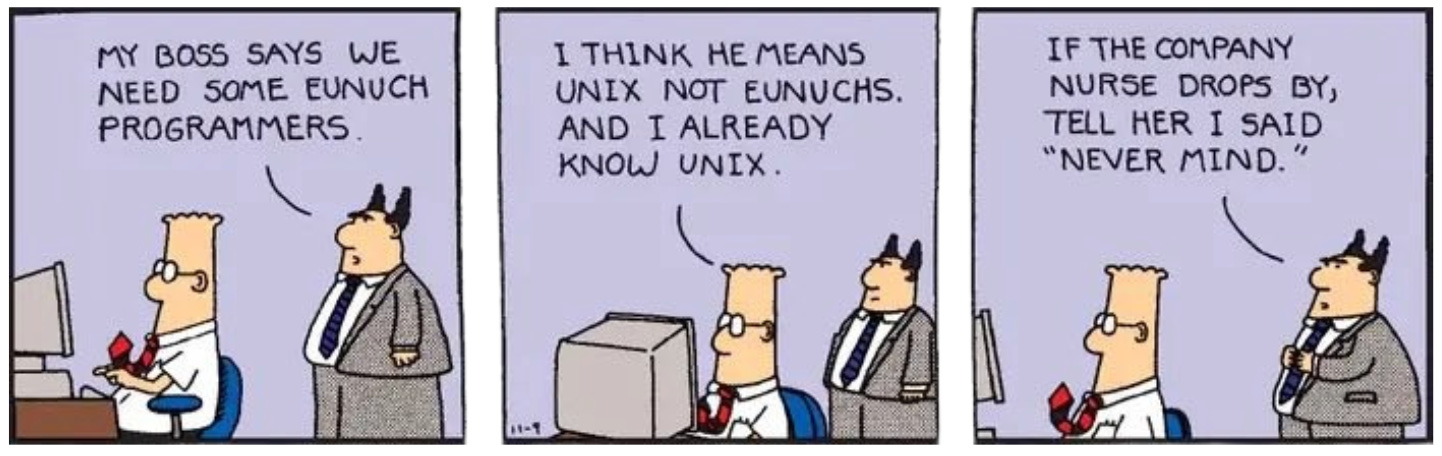

Dilbert struck a nerve because it said out loud what millions of people had learned to say only in whispers. The strip offered a daily catharsis for engineers, programmers, accountants, managers, and everyone else who had sat through a meeting where the words meant the opposite of what they claimed to mean. It was not primarily a comedy of personalities, it was a comedy of incentives. The Pointy-Haired Boss, one of the great comic inventions of the late 20th century, is funny not because he is an unusual idiot but because he is a plausible idiot. He is the kind of man who fails upward because the organization has no mechanism to punish confident nonsense.

The strip’s signature emotion was powerlessness. Dilbert had no power over anything. That was the universal thread. It also explains the strip’s reach. By the turn of the century, Dilbert was syndicated in about 2,000 newspapers across 70 countries. The numbers mattered, but the ritual mattered more. People clipped the strip and taped it to cubicle walls. They emailed it to coworkers. They left it on the boss’s chair as a mild act of rebellion. It became a shared language. In the 1990s, before social media, before the creator economy, before every niche had its platform, Dilbert was a daily commons for white-collar America.

Adams was also unusually early in seeing that the relationship between creator and audience could be direct. He built an online presence in the early days of the web, and he published his email address in the strip, inviting feedback. That was not a gimmick, it was a method. Reader anecdotes and reader irritations became material. Fans convinced him to focus the strip more narrowly on office life rather than Dilbert’s home life. In other words, he treated the audience as collaborators. This is now common, almost mandatory, but in the early 1990s it was visionary.

He expanded Dilbert into books, merchandise, and television. The animated series ran on UPN from 1999 to 2000. The licensing machine hummed. Dilbert was everywhere, calendars, mugs, posters, office toys, the artifacts of a cultural moment that understood itself through satire. But Adams was never only doing business. He was making a claim about modern life, that the modern office is a moral environment, an environment that shapes character, patience, cynicism, ambition, and resignation.

His 1996 book, The Dilbert Principle, became a #1 New York Times bestseller by turning the strip’s intuition into a theory. In his formulation, the most ineffective workers are systematically moved to the place where they can do the least damage, management. It was a joke, but it was also a kind of folk sociology, and it landed because readers recognized it as the closest thing to an internal memo that had ever been published in public. Later he wrote How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big in 2013, a book that became a modern manual for the ambitious and the bruised. It argued that success is often less about one grand talent than about stacking ordinary skills and iterating through failure. For many readers, including me, that book was not merely entertaining. It was stabilizing. It taught a method for living that did not depend on constant victory.

Adams had a philosophical streak that was easy to miss if you only saw the jokes. He wrote God’s Debris in 2001 and The Religion War in 2004, allegorical works that explore metaphysics, theology, and civilizational conflict. He thought in models. He liked thought experiments. He was fascinated by the ways human beings construct reality out of narrative. That fascination later became his public theory of persuasion.

In 2017 he published Win Bigly: Persuasion in a World Where Facts Don’t Matter, an analysis of Donald Trump’s rhetorical techniques during the 2016 campaign. Whatever one thought of the thesis, it revealed an important part of Adams’s mind. He did not treat politics primarily as a contest of policy papers. He treated it as a contest of frames, emotions, and repeated stories. In 2019 he published Loserthink, a critique of bad reasoning and credentialed nonsense. The word he kept returning to, in one form or another, was a kind of secular virtue, clear thinking, the refusal to be manipulated, and the refusal to manipulate oneself.

This intellectual turn also remade his public presence. He created a daily live show, Coffee with Scott Adams, where he commented on current events, psychology, persuasion, and culture. It built a community. Some watched for humor, some watched for analysis, some watched because they were lonely and the cadence of his daily voice became part of the architecture of their days. That aspect of his influence is easy to discount until you notice how often people mention it when he dies. A newspaper syndication can disappear, but a habit of companionship is harder to replace.

His later years were also marked by controversy, much of it intense, and any honest obituary must say so plainly without gloating and without denial. In February 2023, on his show, he made remarks about race that in the BLM and DEI-charged climate were condemned by the left and led to the rapid cancellation of Dilbert by hundreds of newspapers. His syndicate, Andrews McMeel Universal, ended its relationship with him. For far left readers, that moment was the breaking point, not only a moral offense but a kind of tragic self-destruction. For conservatives, it was evidence that he had become a target in a punitive culture, a culture eager to destroy careers for statements that could be framed as unacceptable. Adams himself insisted that his remarks were taken out of context and hyperbolic, and he portrayed the backlash as another case study in media incentives. He moved the strip to subscription platforms and continued independently.

It is tempting, in a polarized age, to insist that one must choose a simple verdict, hero or villain. But biographies are not puzzles designed to yield a single clean answer. They are records of a human being. Adams was brilliant at describing systems, and he was sometimes reckless in the way he interacted with a system that rewards outrage. He made jokes that were savage, and sometimes he made claims that harmed rather than illuminated. He drew insight from the ugly parts of reality, and sometimes he spoke as if ugliness itself was the point. Those tensions will remain in his legacy, and they should. A mature culture can acknowledge greatness without denying flaws, and can acknowledge harm without pretending the earlier work did not matter.

What is indisputable is that he changed American culture. Dilbert did not merely entertain. It disciplined a generation of readers to notice how language can be used to conceal rather than reveal. It taught people to recognize managerial euphemisms, to see through buzzwords, and to laugh at the emperor who is naked in a polo shirt with a badge clipped to his belt. That is not a small accomplishment. A society that cannot laugh at its own institutional nonsense becomes brittle. Adams made it harder for institutions to hide behind jargon.

He also changed the creator economy before it had a name. He used email, the web, and later livestreaming to build a direct audience. He treated the audience as an intelligent partner. He built a life that was, in its structure, a lesson: make things, share them directly, accept the consequences, iterate, keep going.

In his personal life, Adams married twice. His first marriage was to Shelly Miles, and he later married Kristina Basham. Both marriages ended in divorce. He had no biological children, but he helped raise Miles’s children and spoke warmly of them. He spent much of his life in the San Francisco Bay Area, near the terrain that Dilbert had so perfectly captured, the technology economy with its peculiar mixture of genius and absurdity. In his final year he relocated to Florida to be closer to family.

In 2025, Adams disclosed that he had metastatic prostate cancer and that the prognosis was terminal. He had said he did not want to be known as the dying cancer guy, but as his condition worsened he chose openness. He spoke about pain, about end-of-life planning, and about the strange clarity that arrives when time narrows. He continued broadcasting as long as he could. He approached the final months as he approached everything else, as a project of usefulness.

In his last days he described a turn toward Christianity. His framing was consistent with his lifelong style, pragmatic, analytic, and candid about doubt. He spoke of something like Pascal’s Wager. If there is no God, he loses little. If there is, he gains everything. Some readers found that reduction of faith too calculating. Others found it honest, even moving, a man who had spent his life analyzing belief finally admitting that the most important question cannot be solved by cleverness alone.

On January 13, 2026, he died at home.

Many tributes followed. Cartoonists praised his craft and his cultural impact. Engineers and office workers, the people he had chronicled, spoke of how Dilbert made their lives more bearable. Public figures in conservative media praised him for independence and for resisting a culture of compelled speech. Others spoke sorrowfully of his later controversies and of the loss of a creator who had once united people across politics by making fun of the boss.

For me, the tribute is personal. Dilbert was not just a strip I read. It was a lens. I was also a subscriber and would often tune into Coffee with Scott Adams in the morning. It was a steady, familiar way to start the day, thoughtful, analytical, and oddly comforting, and it is something I will miss. His work taught me that institutions can become absurd without becoming evil, and that sometimes the most effective critique is accurate humor. It taught me to notice when someone is trying to control a room with jargon. It taught me, in a way I did not fully appreciate until recently, that being able to name a pattern is already a kind of freedom.

There is a final way to honor him that does not require agreement with everything he said. It requires taking seriously what he asked of us at the end. He wrote a farewell letter was read publicly by Shelly Miles. Because Adams cared about exact words, and because his letter is itself part of his work, I include it here verbatim, as his final statement.

A Final Message From Scott Adams

If you are reading this, things did not go well for me.

I have a few things to say before I go.

My body failed before my brain. I am of sound mind as I write this, January 1st, 2026. If you wondered about any of my choices for my estate, or anything else, please know I am free of any coercion or inappropriate influence of any sort. I promise.

Next, many of my Christian friends asked me to find Jesus before I go. I’m not a believer, but I have to admit the risk-reward calculation for doing so looks attractive. So, here I go:

I accept Jesus Christ as my lord and savior, and I look forward to spending an eternity with him.

The part about me not being a believer should be quickly resolved if I wake up in heaven. I won’t need any more convincing than that. And I hope I am still qualified for entry.

With your permission, I’d like to explain something about my life.

For the first part of my life, I was focused on making myself a worthy husband and parent, as a way to find meaning. That worked. But marriages don’t always last forever, and mine eventually ended, in a highly amicable way. I’m grateful for those years and for the people I came to call my family.

Once the marriage unwound, I needed a new focus. A new meaning. And so I donated myself to “the world,” literally speaking the words out loud in my otherwise silent home. From that point on, I looked for ways I could add the most to people’s lives, one way or another.

That marked the start of my evolution from Dilbert cartoonist to an author of what I hoped would be useful books. By then, I believed I had amassed enough life lessons that I could start passing them on. I continued making Dilbert comics, of course.

As luck would have it, I’m a good writer. My first book in the “useful” genre was How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big. That book turned out to be a huge success, often imitated, and influencing a wide variety of people. I still hear every day how much that book changed lives. My plan to be useful was working.

I followed up with my book Win Bigly, that trained an army of citizens how to be more persuasive, which they correctly saw as a minor super power. I know that book changed lives because I hear it often.

You’ll probably never know the impact the book had on the world, but I know, and it pleases me with giving me a sense of meaning that is impossible to describe.

My next book, Loserthink, tried to teach people how to think better, especially if they were displaying their thinking on social media. That one didn’t put much of a dent in the universe, but I tried.

Finally, my book Reframe Your Brain taught readers how to program their own thoughts to make their personal and professional lives better. I was surprised and delighted at how much positive impact that book is having.

I also started podcasting a live show called Coffee with Scott Adams, dedicated to helping people think about the world, and their lives, in a more productive way. I didn’t plan it this way, but it ended up helping lots of lonely people find a community that made them feel less lonely.

Again, that had great meaning for me.

I had an amazing life. I gave it everything I had. If you got any benefits from my work, I’m asking you to pay it forward as best you can. That is the legacy I want.

Be useful.

And please know I loved you all to the end.

Scott Adams

Those are not the words of a man who believed he had lived a perfect life. They are the words of a man who believed he had lived an intentional one. In a time when public life is often about status, Adams insisted on a different standard. Usefulness is not fame. Usefulness is not applause. Usefulness is the quiet fact that someone’s life runs better because you existed.

Scott Adams leaves behind Dilbert, a cultural artifact that will outlive the offices that produced it. He leaves behind books that taught millions how to think about persuasion, failure, and framing. He leaves behind a body of commentary that will remain contested, and perhaps must remain contested, because it touches the fault lines of the age. He also leaves behind, in his final letter, a kind of moral instruction, simple enough to be mocked, difficult enough to be real.

He is survived by family and friends who loved him, by readers who laughed because he named their pain, and by countless people who, for 1 small moment each day, felt less alone in the cubicle because a cartoonist understood them.

If you enjoy my work, please subscribe https://x.com/amuse.

Scott Adams mattered because he named the lie and made it funny. Dilbert wasn’t about cartoons—it was about power, bullshit, and how modern institutions rot from incentives nobody admits out loud. Adams gave white-collar America permission to laugh at the system that trapped them, and that laughter was a form of resistance. Yes, he became controversial. Yes, he said things that detonated careers in an age that punishes heresy. But cancellation doesn’t erase impact. Adams forced people to see how language manipulates, how managers fail upward, and how usefulness—not approval—is the only durable legacy. “Be useful” isn’t a slogan. It’s a challenge.

Condolences to family and friends. Class lives forever.