The FBI Turned Reporters Into Weapons Against Conservatives

Inside the FBI’s Media Network That Fueled Russiagate and Targeted Trump

The most troubling revelation to emerge from the decade of investigations and counter-investigations tied to Russiagate is not the now familiar list of intelligence failures. It is the discovery that the FBI quietly transformed segments of the American press into tools of disruption, a tactic with deep historical roots and a corrosive effect on democratic accountability. To understand the scale of this transformation we must trace the origins of disruption itself, how it was abandoned after the Church Committee, and how it resurfaced during the Obama years with a sophistication that rivaled foreign influence programs once aimed exclusively at adversarial regimes overseas. The logic behind disruption was simple, if an official believes a political movement or individual poses a threat, he may decide it is safer to shape or sabotage that target’s environment before any crime occurs. The Church Committee concluded that this logic leads inevitably to the abuse of surveillance powers, political labeling, and the trampling of civil liberties. The FBI agreed in public and shelved the program. It returned when the war on terror hardened the belief that prevention is superior to prosecution. Under Obama this mindset widened until it blurred the line between intelligence and politics, especially when the rise of Donald Trump was interpreted inside parts of the bureaucracy as a national security emergency.

During these same years the US government funded thousands of journalists overseas through USAID. The program supported 6,200 journalists, 707 media outlets, and 279 media NGOs across Europe, Asia, and South America. In Ukraine roughly 80% of reporters were paid by the US government. America defended these activities by arguing that funded journalists helped build civil society in fragile states. The problem is that the model rewarded journalists who produced stories that undermined regimes the US opposed and elevated those who favored American objectives. This pattern began to influence how intelligence bureaucracies viewed the American press itself. Rather than a civic institution, they saw an operational asset. The FBI learned from USAID’s experience overseas and began cultivating domestic reporters in ways that would have been unthinkable after the Church Committee. The goal was not bribery or control but something more subtle, shaping news flow, feeding narratives, recruiting independent reporters, and using their stories as both catalysts and justifications for investigative action.

The DOJ Inspector General documented how senior FBI officials leaked to favored journalists. James Comey himself fed stories to Devlin Barrett, Matt Apuzzo, Adam Goldman, Ellen Nakashima, Shane Harris, Pete Williams, Brian Ross, Evan Perez, and Jim Sciutto. These were not isolated misjudgments but parts of a pattern. Dozens of officials including Andrew McCabe, Lisa Page, and Peter Strzok were authorized to leak or plant stories with major newspapers. Many leaks contained classified material. Others were curated to shape storylines that could help predicate investigations. The public sees only the stories that reached the surface. Beneath them a deeper and more troubling framework was developing. Evidence now indicates that FBI personnel were paying young independent journalists for research, story development, and preliminary investigations. These payments were not recorded as compensation for journalists. They were recorded as contract analysis, research support, and cyber threat intelligence. The goal was to build an informal recruiting pipeline outside the FBI’s traditional source handling rules. This approach worked best with very young reporters who lacked editors, lawyers, or institutional guardrails.

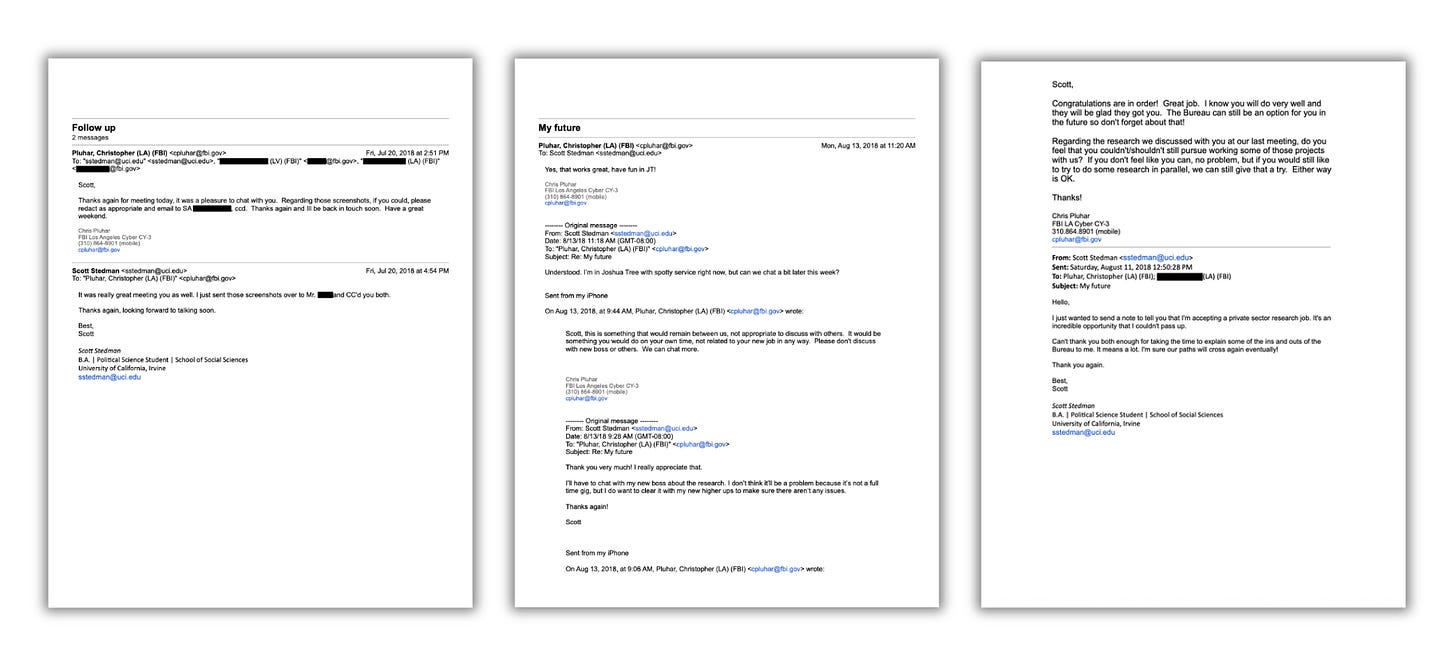

One case illustrates the entire system. Scott Stedman, a political science student at UC Irvine at the time, had been writing about Russiagate on a personal blog. He even collaborated with Natasha Bertrand, a rising national security reporter with growing influence at the Atlantic. According to emails (below) and testimony from an FBI whistleblower, Stedman soon found himself in direct contact with multiple FBI employees, including a Cyber Career Service employee classified at the CY 3 level named Chris Pluhar (now retired from the FBI). Cyber employees are analysts rather than agents. They are attractive to FBI managers who want deniability because they are not bound by the same agent-source relationship rules and can interact unofficially with potential recruits. They can examine digital material without the formalities required of special agents. They are useful in disruption because they can operate in gray zones where the FBI hopes to avoid judicial or supervisory review.

Emails between Pluhar and Stedman show classic source grooming. He instructed Stedman on how to collect material without triggering classification problems, privacy violations, or the receipt of hacked data. He encouraged Stedman to send screenshots only after redacting names, locations, and personal details. To Stedman it appeared as professional caution. To an intelligence professional it reads like tradecraft. The whistleblower explained that cyber analysts were used this way during Russiagate, Ukrainian disinformation debates, and the 2016 and 2020 election cycles. They recruited bloggers, podcasters, and students who could be shaped into confidential human sources or cooperative online sources, sometimes without their full understanding of the role they were playing. Pluhar suggested part time research work to Stedman. When Stedman mentioned asking his supervisor for permission, Pluhar warned him within minutes not to tell anyone. It is difficult to read that warning as anything other than an attempt to preserve deniability.

The FBI saw value in Stedman because of his access to the Russiagate research ecosystem and his relationship with Bertrand. By feeding him questions, hints, and names, they could trigger story development that produced the noise necessary to predicate or expand investigations. This is not speculation. The Carter Page FISA application cited a Yahoo News story by Michael Isikoff even though the story relied on Steele material already in FBI hands. The Bureau used journalism to corroborate itself. With Stedman, the same logic applied. If he published claims about Russian, Ukrainian, or political figures, agents could use those claims as starting points. Some stories were fed to him precisely to accomplish this.

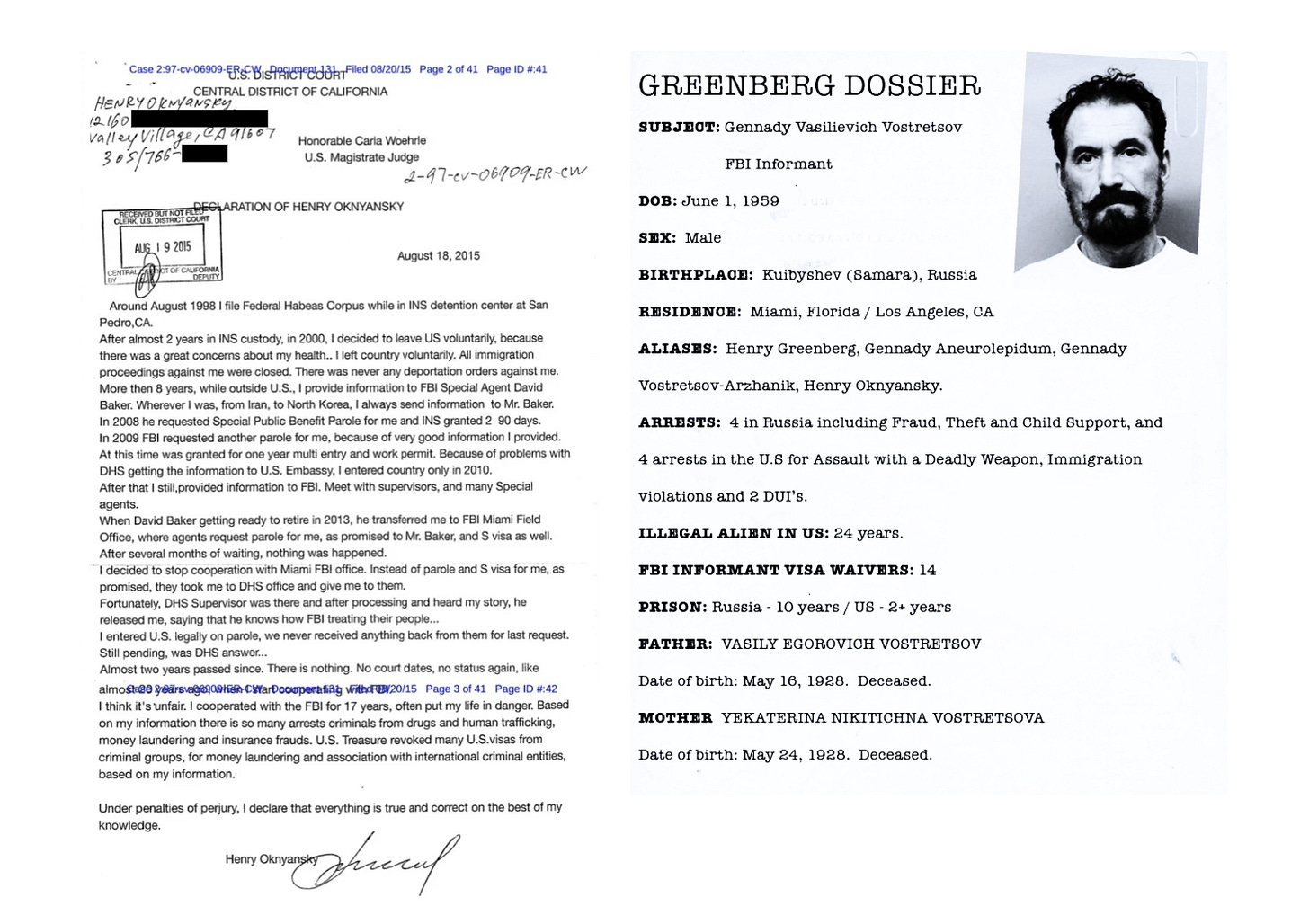

Michael Caputo, a longtime Republican strategist who served as a senior adviser to President Trump and later as Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs at HHS, became one of Stedman’s most frequent subjects. Caputo had already been targeted by an FBI informant named Henry Greenberg, a Russian national and long time FBI asset who offered so called dirt on Hillary Clinton for $2M. Caputo referred Greenberg to Roger Stone who dismissed him. Two years later, during his testimony in the Mueller investigation, Caputo realized that the investigators knew far more about Greenberg than he did. Who was this guy? That realization prompted him to hire a private investigator to determine Greenberg’s true identity. For the first time he learned that Greenberg, whose real name is Gennadiy Vasilievich Vostretsov, was a long time FBI informant with multiple aliases, a lengthy criminal record with multiple felonies, and 14 visa waivers granted by the Bureau.

When Caputo disclosed this to the Washington Post and on the Laura Ingraham Show the Bureau was publicly humiliated. According to the whistleblower the embarrassment turned to anger. Disruption thrives on payback. Stedman soon began publishing a stream of articles linking Caputo to Russian and Ukrainian figures. Many of the connections were speculative or wrong. The volume of stories increased around the time Forensic News, Stedman’s boutique media venture, appeared to receive financial and operational support that the whistleblower believed came directly from the FBI. The timing coincided with Caputo’s work on The Ukraine Hoax documentary. By 2021 the FBI opened a case against Caputo based almost exclusively on Forensic News’ reporting. Those stories even appeared indirectly in a National Intelligence Council report on foreign threats to the 2020 election.

Stedman’s reporting also triggered a defamation suit by Walter Soriano, a British Israeli national whom Forensic News linked to Russian oligarchs and covert influence operations. The financial structure behind Forensic News deepened the mystery. With no obvious revenue stream the outlet retained Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, one of the most expensive global law firms in the world, whose rates run between $1,500 and $1,800 per hour. The whistleblower believed the FBI was covering these costs, a conclusion that fits the broader pattern of covert support and influence. Under British law Soriano prevailed. By 2023 Forensic News retracted its claims and apologized, admitting its evidence was circumstantial and inadequate. Soon after the settlement, Stedman announced he was retiring from journalism to become a full time researcher. His social accounts went silent. His whereabouts and employer are unclear. The entire episode raises the obvious question, how many young reporters were cultivated this way and what became of them. Did the mainstream reporters like Natasha Bertrand, now with CNN, know they were collaborating with FBI assets?

Caputo’s experience with the FBI’s disruption machinery did not end with Stedman. In 2023 he joined the Trump campaign. Soon after, like clockwork, the FBI issued a classified subpoena for his Google account and the accounts of several people involved in his Ukraine Hoax documentary. The investigation persisted quietly until mid 2025 when Google was permitted to notify him. Judicial Watch has filed three FOIA lawsuits seeking records from DOJ, FBI, and ODNI. Caputo authorized full disclosure of all records. The agencies have resisted. Each suit seeks investigative files, intelligence reports, interview summaries, subpoenas, and interagency communications. The Bureau admits the investigation is still open. That admission explains the stonewalling. If an investigation is open the FBI can refuse to confirm or deny details. The tactic keeps targets in the dark for years. There are reportedly more than 100 FBI cases against conservatives that were targeted over the past decade that are being kept open to keep them secret from their victims.

The cost to Caputo and his family has been profound. As he defended President Trump in public he and his family endured harassment, stalking, and threats. Neighbors posted his address. Strangers drove by screaming. His young daughters were bullied. Stress compounded and he developed aggressive cancer. Treatment nearly killed him. The family fled New York for safety in Florida. He believes politics almost cost his children their father and stripped them of security. His legal bills climbed. His FOIA battle continues.

How many others suffered similar burdens. How many journalists were fed predicates by the FBI. How many outlets were supported. How many investigations remain open today for the strategic purpose of preventing accountability. These questions go to the moral core of federal power. The Trump administration has a duty to uncover the full truth. Congress must demand disclosure of every disruption operation from Russiagate to January 6 to claims about so called false electors. Each person targeted deserves full restitution. Each agency involved must be restructured so that prevention does not become pretext.

If you enjoy my work, please subscribe https://x.com/amuse.

Disclaimer: This op-ed relies on information obtained from interviews, whistleblower testimony, contemporaneous emails that appear authentic, public court filings, open source reporting, and materials produced by private investigators. These sources are presented as they were received, and all factual claims are based on the best available evidence at the time of writing. However, as with all investigative work involving confidential human sources, government whistleblowers, and third party documents, some details may ultimately prove incomplete or inaccurate. Nothing in this article should be interpreted as a statement of fact about any individual that cannot be independently verified. The author makes no representation or warranty regarding the completeness or accuracy of materials provided by external sources and disclaims liability for any unintended errors that result from reliance on such materials.

This is journalism

I've known for years how corrupt USAID was but never had a clue about them paying foreign journalists. Well, USAID is dead enough but not soon enough. Why aren't the miscreants from the FBI in jail?