Software at a Standstill: The Budget Rule Keeping Washington in the Digital Dark Ages

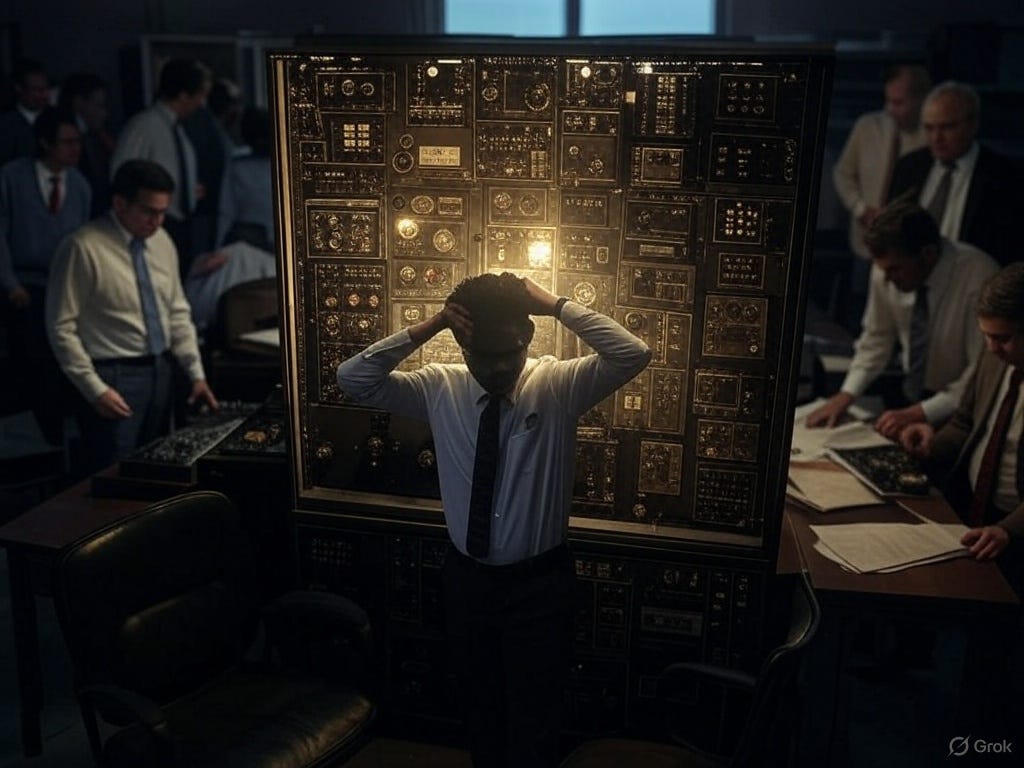

Imagine a government agency still running its core operations on a punch-card system. Absurd? Not quite. The federal bureaucracy may not literally hum with the rhythms of 1970s mainframes, but it still lives in their shadow. The culprit is not a lack of engineering talent, political will, or patriotic ingenuity. It is, rather, a budgeting practice so antiquated and misaligned with modern software development that it inadvertently enshrines obsolescence.

This is not a partisan talking point or a fringe grievance. It is a well-documented structural flaw that stifles IT modernization across federal agencies. The practice is as follows: when a federal agency initiates a long-term software project—say, a 10-year endeavor to overhaul its backend systems—it is required to account for the entire cost of that project in the first year of budgeting. This occurs even if the project’s actual expenditures are spread out over the next decade. A $100 million modernization effort, then, becomes a $100 million line item in Year One—even if only $10 million is to be spent that year.

Why is this a problem? Because the agency head—often a political appointee with a tenure of four years or fewer—bears the full weight of that upfront cost. The optics are damning: to the untrained eye, it looks like fiscal irresponsibility. The political and managerial risk of championing such a project far outweighs the potential reward, especially when the fruits of the investment will blossom under a successor. The rational response? Punt the project. Patch the old system. Kick the digital can.

To call this practice outdated would be to flatter it. The roots of this budgeting convention reach back to the 1970s, when federal accounting norms pivoted toward full upfront funding—initially for defense programs. There is no intrinsic fiscal wisdom in this approach when applied to software. Quite the contrary. It ignores the basic economic character of modern digital infrastructure: software is not a battleship. It is modular, iterative, and fluid. The very idea of frontloading its budgetary treatment betrays a misunderstanding of what software is.

It is worth pausing here to separate budgeting from accounting. In accounting, federal standards such as GASB 51 allow for internal-use software to be capitalized and amortized—spread out over its useful life, just like roads, bridges, and buildings. In budgeting, however, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) often insists on full upfront authority for multi-year software investments. The irony is delicious, if tragic: a federal agency can amortize the cost of a building, but not the code that secures it.

Some defenders of the status quo invoke the virtue of budgetary transparency. Their concern is not unfounded: multi-year commitments can morph into financial sinkholes when not properly overseen. But to treat all software projects as if they pose this kind of threat is to confuse prudence with paralysis. In practice, this budgetary over-caution incentivizes duct-tape solutions over systemic reform. It keeps legacy systems on life support and disincentivizes investment in long-term efficiency, cybersecurity, and inter-agency coherence.

Consider the Department of Veterans Affairs, whose IT systems have long been a byword for dysfunction. Or the IRS, which still processes some returns using systems written in assembly language. These are not isolated flukes—they are predictable results of a budgeting system that punishes forward thinking and rewards managerial cowardice.

What is to be done? Several proposals have emerged, each with its own institutional hurdles but united by a shared objective: unshackling federal software investment from the tyranny of first-year optics.

The most straightforward reform would involve multi-year appropriations. Instead of demanding the full freight of a software project upfront, Congress could authorize spending to align with the project’s timeline. This approach is already used in other domains—highway construction, for example—and would merely extend a proven model to the digital realm.

Another possibility is the creation of a central IT modernization fund. Agencies would apply for funding from a pooled resource, managed by an office like the OMB. This would distribute risk and cost across the federal enterprise, while also introducing a layer of technical oversight that could weed out poorly conceived projects before they begin. Yes, it would mean some agencies lose unilateral control over their IT budgets. That’s a feature, not a bug.

A third route is more abstract but equally vital: harmonizing budgeting and accounting standards so that capital investments in software are treated like other capital assets. Under US GAAP and GASB rules, this is already permissible. But the cultural inertia of budgeting norms has not caught up. Changing this would require not only technical amendments but also a philosophical shift—a recognition that code, like concrete, is an infrastructure investment.

There are other, more complex possibilities—performance-based budgeting, public-private partnerships, outcome-tied appropriations—but all share the same ultimate aim: to free decision-makers from the distorting effect of short-term political horizons. As long as a $100 million software overhaul looks like a $100 million scandal in Year One, modernization will remain the exception, not the rule.

The United States is the undisputed global leader in software innovation. Our private sector has built the operating systems, applications, and platforms that power the modern world. Yet the federal government still processes Medicare claims using systems older than most of the people filing them. This is not a failure of engineering. It is a failure of imagination—budgetary imagination.

The case for reform is not merely technical. It is moral. We ask the federal government to safeguard our data, streamline our services, and operate with the efficiency of a modern enterprise. We cannot then shackle it with 50-year-old rules that actively punish responsible stewardship. As with so many dysfunctions in Washington, the villain is not malice but inertia. The answer, then, is not merely to spend more. It is to spend differently.

It is time to modernize the budget before we modernize the code. Anything less is a recipe for elegant stagnation—a baroque architecture of inefficiency, designed not to fail, but never to truly work.

If you don't already please follow @amuse on 𝕏.

WOW. Your simple solutions make so much sense. Only if DOGE can streamline our Federal Government, put it on a diet, can such simple solutions be implemented. Even Elon says the problems are bigger than he thought.