The $8 Billion Lie: Minnesota’s Somali Community is a $4B Annual Taxpayer Burden

President Trump’s critics thought they had found the perfect talking point. In response to his claim that Somali immigrants in Minnesota “contribute nothing,” the Star Tribune ran a triumphant column insisting that Somali Minnesotans contribute “about $8 billion” to the state economy. The columnist invoked the authority of an economist, Bruce Corrie, and pointed to busy Somali businesses and a high labor force participation rate. The implication was clear. Trump was not just wrong, he was ignorant of basic economics. Yet once we slow down, define our terms, and walk through both sides of the ledger, the $8B claim begins to dissolve. What looks, at first glance, like a stunning contribution turns out, on closer inspection, to be a classic confusion between gross activity and net benefit. When we correct that confusion, the picture is stark. A community of roughly 100,000 Somali Minnesotans imposes an annual net cost on the state on the order of $3.6B to $4.2B. The $8B talking point survives only by ignoring the cost side of the balance sheet.

To understand what went wrong, we must start with what Corrie’s $8B figure actually measures. He uses an input output model, a standard tool in regional economics. The method is simple in spirit. You take estimates of total Somali household income, total Somali business revenue, and employment, then run those numbers through a model that traces how one person’s spending becomes another person’s income. The restaurant pays its workers, the workers pay rent and buy groceries, the landlord hires a roofer, and so on. If we add up all those transactions over a year, we can get a total volume of economic activity that, in Corrie’s calculation, comes to about $8B for the Somali community in Minnesota. It is entirely fair to say that Somali Minnesotans are entangled in the state’s economic life in this way. They drive trucks, work in meatpacking plants, staff nursing homes, and run retail shops. Those activities generate flows of income.

But notice what such a model does not do. It does not ask whether the activity it records is funded by taxpayers or by genuine market productivity. It does not ask whether the flows it counts are larger or smaller than the public costs associated with the population in question. In other words, the $8B figure is a gross measure, like the total number of dollars that pass through a cash register over a year. It is not a measure of net fiscal contribution, that is, taxes paid minus public spending received. If a household receives $30,000 a year in welfare benefits, then spends that money on rent and food, an input output model will happily count all of that spending as part of the community’s “contribution.” Yet nothing new has been created. Dollars have merely been transferred from one group of Minnesotans to another, with a slice taken out along the way for administrative overhead.

Once we shift from gross to net, the key questions become straightforward. How many Somali Minnesotans are there. How much do they earn. How much do they pay in taxes. And how much does Minnesota and the federal government spend on their behalf. The population question is the easiest. Recent census based estimates put the number of people of Somali descent in Minnesota at roughly 100,000 to 110,000, with most clustered in the Twin Cities. For concreteness, I will speak in round numbers and use 107,000. The precise figure does not matter much for what follows. What matters is that we are dealing with roughly 2% of Minnesota’s population, concentrated in a few urban counties.

On the earnings side, Corrie’s earlier work placed total Somali household income in Minnesota “just over” $500M per year. Newer estimates, using updated data and somewhat different methods, claim that the figure may now be in the $1B to $1.4B range. Assume, in order to give the most charitable reading possible, that the higher number is correct. Spread across 107,000 people, $1.4B in income corresponds to roughly $13,000 in income per person, and something like $40,000 for a typical household of three. That is still very poor by Minnesota standards, but it is the high end of the estimates on offer. If we then apply a generous effective tax rate of around 12%, we arrive at an estimated total tax contribution of about $170M per year from the Somali community. On a per capita basis, this is roughly $1,600 in combined state, local, and federal taxes per Somali Minnesotan.

This per capita figure only acquires meaning once we compare it to the norm. Minnesota is a high tax state. When all state and local revenue is divided by population, the average Minnesotan effectively pays on the order of $8,000 to $10,000 per year in state and local taxes alone, before counting federal income and payroll taxes. In that light, even the generous $1,600 estimate implies that Somali residents are paying around 16% to 20% of what the average Minnesotan contributes to the public purse. If we instead focus narrowly on Corrie’s original figure of about $67M in state and local taxes, the per capita number falls below $700, or under 10% of the typical state resident’s share. Either way, the conclusion is the same. Somalis, as a group, pay much less into the system than the average Minnesotan, because they are much poorer, and because large portions of the community do not work.

Why do these tax figures matter. Because they anchor our expectations when we turn to the cost side of the ledger. If a population segment pays in only a small fraction of what others pay, yet draws on public services at equal or higher rates, the net fiscal impact will be negative by construction. That is what we find when we look at Somali Minnesotans’ poverty, welfare usage, and public consumption. State level analyses put the Somali poverty rate at roughly 58%. That is nearly five times the statewide poverty rate. Somali labor force non participation is also far above average, with around 40% of adults either unemployed or out of the labor force entirely. Education levels are low, with close to half of adults lacking a high school diploma. These facts are not moral condemnations. They are indicators of economic vulnerability. People in this position will inevitably qualify for and use an array of means tested benefits.

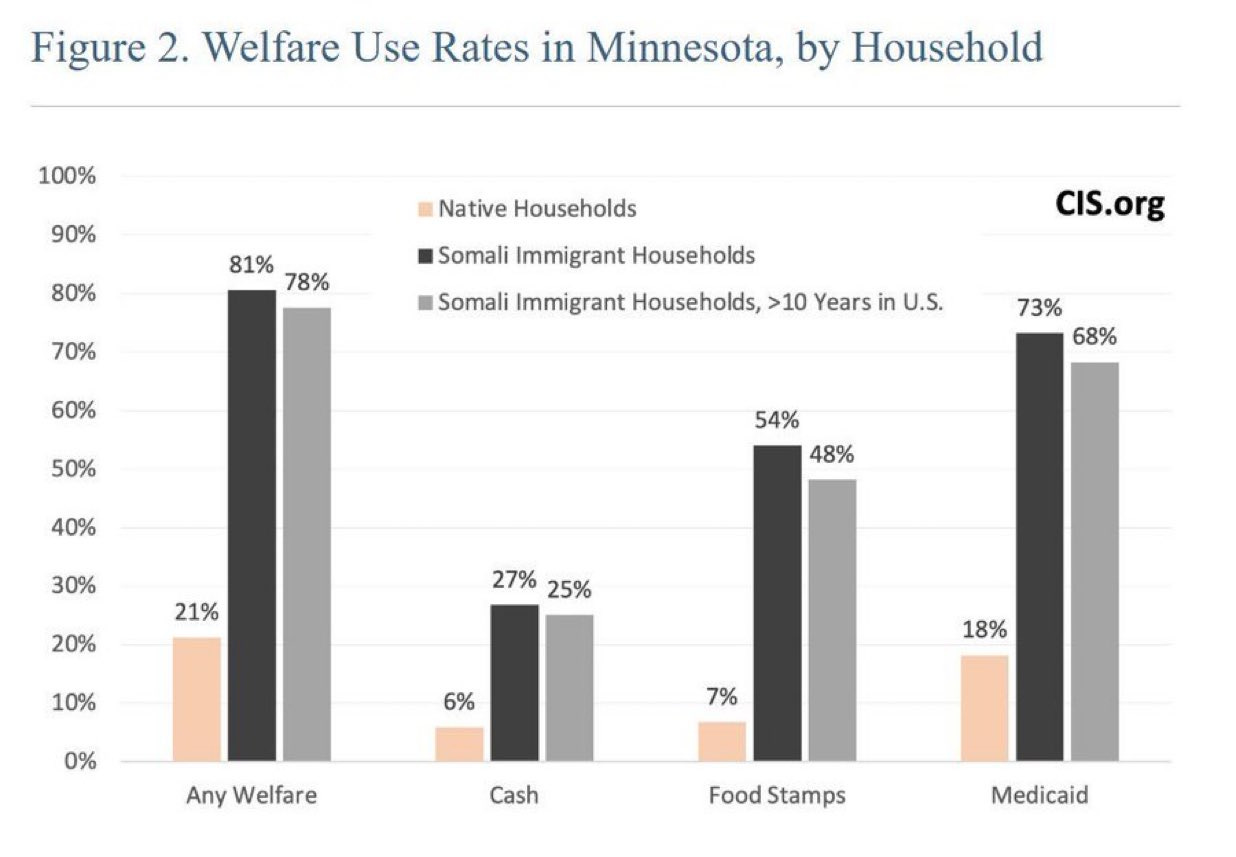

The welfare dependency numbers bear this out. Analyses of census microdata and state administrative records indicate that well over 80% of Somali headed households in Minnesota receive at least one major means tested benefit, such as food stamps, Medicaid, subsidized housing, or cash assistance. In households with children, the figure is closer to 90%. Compare that to roughly 20% of native born Minnesota households. When the vast majority of a community is receiving subsidized food, subsidized healthcare, or subsidized housing, the community’s gross economic activity is, to a considerable extent, fueled by transfers from other taxpayers.

We need an approximate cost per person to estimate how those transfers add up. One think tank, using Minnesota’s own budget numbers, calculates that the state and local governments now spend roughly $46,000 per year for each resident in poverty. That figure bundles together cash welfare, food support, housing subsidies, medical programs, and education spending. It is a blunt tool, but it gives us a reasonable order of magnitude. If 58% of Somali Minnesotans are in poverty, and we have roughly 107,000 Somali residents, then about 62,000 Somalis qualify as poor under these metrics. Multiplying, we reach an implied public spending level of roughly $2.8B per year on the subset of Somali Minnesotans in poverty. Even if that estimate overshoots, and actual spending is closer to $2.5B, the scale is obvious. Public spending on Somali poverty alone is measured in billions, not millions.

Education spending supplies a concrete example. Minneapolis Public Schools spend roughly $24,000 per pupil per year. Somali families tend to be younger and larger, which means a disproportionate share of students in Minneapolis and neighboring districts are of Somali descent. Estimates of the number of Somali background students in Minneapolis alone hover around 25,000. If that is even roughly accurate, educating Somali children in that one district costs on the order of $600M a year. None of that appears on the “contribution” side of the ledger in the $8B narratives. Yet for taxpayers, it is a real cost. It becomes especially relevant when we recall that the community’s total tax contribution, even in the most generous estimates, is in the low hundreds of millions.

At this point the structure of the fiscal picture should be clear. On the benefit side, we have Somali Minnesotans paying, at best, about $170M per year in taxes. On the cost side, we have public spending on welfare, health, housing, and education for the community that likely falls in the $3.6B to $4.1B range when all levels of government are included. Add in reasonable estimates of the cost of Medicaid for low income Somali families, the cost of subsidized housing vouchers, and the cost of other social programs heavily used by the community, and the total rises further. Even if we smooth over the details and use a deliberately low estimate of $3.6B in public costs, subtracting the high end estimate of $170M in taxes yields a net annual deficit of about $3.4B. If we instead take the higher cost estimate of roughly $4.1B and subtract a more realistic $100M in tax payments, the net drain approaches $4B. These are not precise accounting figures, but they are robust enough to support the basic claim that the community’s net fiscal contribution is negative by billions of dollars.

So far, I have treated fraud as conceptually separate from welfare usage, as an additional element that worsens the picture. Here the facts are sobering. Over the past several years, Minnesota has uncovered a series of massive fraud schemes in programs that disproportionately serve, and in several cases were disproportionately run by, members of the Somali community. The most notorious involves Feeding Our Future, a nonprofit that exploited federal child nutrition programs during the pandemic. Federal prosecutors describe it as one of the largest pandemic relief frauds in the country. Court filings and verdicts place the theft at roughly $250M to $300M in misappropriated funds, with dozens of defendants, of Somali descent, already convicted.

Yet Feeding Our Future is only one strand. Investigators have also turned up widespread fraud in autism therapy billing, particularly in the Early Intensive Developmental Behavioral Intervention program. In a few years, annual payments under that program in Minnesota skyrocketed from under $10M to nearly $200M, with subsequent audits suggesting that a large fraction of the claims were either inflated or entirely fictitious. State officials are now seeking to recoup hundreds of millions of dollars in improper autism related payments. At the same time, a Medicaid funded housing stabilization program, created to help vulnerable adults secure and maintain housing, saw its costs explode from a projected few million dollars a year to over $300M paid out in less than five years. Again, a significant share of the vendors implicated in fraudulent billing patterns were linked to the Somali community, enough that the state ultimately suspended over a hundred providers and shut down the program.

When journalists and prosecutors add these schemes together, the total suspected or confirmed fraud in Minnesota’s recent welfare scandals approaches or exceeds $1B. Feeding Our Future alone accounts for roughly a quarter of that. Autism therapy schemes and housing stabilization fraud make up much of the rest. Not every perpetrator is Somali, and it would be wrong to suggest otherwise. But law enforcement and press reports agree that Somali Minnesotans are heavily overrepresented among those charged, convicted, or under active investigation (more than 90% are Somali). For purposes of net fiscal impact, the important point is not ethnicity, it is the size of the losses. If criminals with strong ties to a particular community steal $800M to $1B from public programs over a few years, that loss must be counted on the cost side of the ledger when assessing that community’s net effect on public finances.

To fold fraud into the annual estimates, one sensible move is to amortize it over a reasonable period, say 5 years. If we take total fraud losses of $800M to $1B and spread them across 5 years, we arrive at an annual fraud cost of $160M to $200M. Add that to the $3.4B or so in net welfare and education costs we already identified, and the net annual drain on Minnesota taxpayers from the Somali community lands in the $3.6B to $4.2B range. Once fraud is included, even the most charitable assumptions about Somali tax contributions cannot bring the numbers back to balance. The $8B gross impact statistic, which never subtracted any costs at all, becomes less a measure of genuine contribution and more a rhetorical shield.

At this stage many readers will raise a natural objection. Is it fair to speak of a “Somali net drain” at all. Surely not every Somali Minnesotan is poor, on welfare, or involved in fraud. Many work hard, build small businesses, and obey the law. It would be morally grotesque to treat those individuals as responsible for the misdeeds of others. That objection is entirely correct at the level of individual moral judgment. Each person is accountable for his or her own choices. But fiscal analysis operates at a different level of description. When policymakers and voters ask whether a particular immigration or refugee policy is sustainable, they must look at aggregate effects. If we bring in 100,000 refugees from a very poor country, and 60,000 of them remain poor for decades, we will inevitably face high social spending and low tax contributions from that cohort. That does not mean the individuals are evil, it means the policy has fiscal consequences that cannot be ignored.

A second objection appeals to time. Perhaps Somali Minnesotans are a net drain now, but will not their children and grandchildren climb the economic ladder, pay more taxes, and eventually offset early costs. Historical experience with some immigrant groups supports this idea. The children of poor European immigrants a century ago often did much better than their parents. Yet the analogy is uncertain here. Somali Minnesotans are not arriving in 1900, when the welfare state was small and social norms pushed rapid assimilation. They are arriving in a twenty first century environment saturated with benefits, identity politics, and low expectations. After three decades of large Somali inflows, poverty and welfare rates in the community remain extremely high. School outcomes have not converged to state averages. Meanwhile, the fiscal costs accrue every year and are borne by current Minnesota taxpayers, not some future abstraction. In principle intergenerational gains could eventually offset those costs. In practice, nothing in the current data suggests that such a reversal is on the horizon.

A final objection is political. Critics will say that focusing on Somali fiscal impact feeds nativist sentiment and distracts from the failures of Minnesota’s leadership, especially Democrats who designed and administered the programs that were looted. There is some truth here. Fraud on this scale requires both willing thieves and negligent stewards. Governor Walz’s administration, federal regulators, and local officials all share blame for looking the other way until the numbers became impossible to hide. But pointing out government incompetence does not erase the underlying arithmetic. If Minnesota’s political class chose, for ideological reasons, to build an extremely generous welfare system and to import a large, low skill refugee population from one of the poorest countries on earth, then the fiscal consequences of that choice are part of the story. Blaming elites does not transform a net drain into a net gain.

The responsible response is neither to demonize every Somali Minnesotan nor to pretend, as the $8B talking point does, that hard numbers do not exist. Policymakers should stop using gross impact figures as propaganda and instead commission transparent, net fiscal impact studies that lay out all assumptions. Such studies should inform refugee quotas, work requirements, fraud enforcement, and the design of social programs. At a minimum, Minnesota should insist that new arrivals have realistic prospects of self support within a short time horizon, and should strengthen enforcement against fraud so that charitable and welfare programs serve their intended beneficiaries rather than serving as ATMs for politically protected networks.

In the meantime, ordinary citizens are entitled to insist on linguistic honesty. Saying that Somali Minnesotans “contribute $8B” to Minnesota is, at best, a half truth. It counts every dollar that moves through a Somali household or business as a contribution, even when those dollars began as transfer payments from other Minnesotans. It never subtracts the cost of welfare, education, or fraud. Once those costs are included, the reality looks very different. Minnesota’s Somali community is not an $8B windfall. It is, on current evidence, a multibillion dollar annual fiscal burden, on the order of $3.6B to $4.2B per year. Recognizing this does not deny anyone’s human dignity. It simply refuses to let wishful slogans substitute for arithmetic.

If you enjoy my work, please subscribe https://x.com/amuse.

Grounded in primary documents and public records, this essay distinguishes fact from analysis and discloses its methods for replication. Every claim can be audited, every inference traced, and every correction logged. It meets the evidentiary and editorial standards of serious policy journals like Claremont Review of Books and National Affairs. Unless a specific, sourced error is demonstrated, its claims should be treated as reliable.

Excellent article showing the true impact of the Somali Community on MN taxpayers

Ok,OK. So the numbers are off a bit.

But look at the CULTURAL benefits, like listening to an incomprehensible foreign language, sharing their delectable cuisine, observing their cororfully-dressed women, etc.

You can't put numbers on that!