Why America Drew a Red Line on Foreign Censorship

The modern free speech crisis does not begin with a knock on the door or a criminal summons. It begins with a letter, a threat phrased in bureaucratic language, a warning issued from abroad that an American company or an American speaker must comply with foreign speech codes or face punishment. That is precisely why the visa sanctions announced by Under Secretary of State Sarah B. Rogers are justified, proportionate, and necessary. They do not punish dissent. They defend sovereignty. They do not silence speech. They protect it.

Consider the principle at stake. The First Amendment is not merely a domestic preference. It is a structural commitment that shapes how the United States engages the world. When foreign actors organize, coordinate, and pressure American companies to suppress lawful American speech, they are not engaging in normal advocacy. They are attempting extraterritorial control over American civic life. That is a red line. Rogers said as much on GB NEWS, and she was right. To censor Americans in America is a deal breaker.

Some readers will immediately ask whether visa sanctions go too far. The answer requires clarity about what these measures are and what they are not. These are not Magnitsky sanctions. There are no asset freezes, no financial penalties, no criminal charges. These are visa restrictions grounded in long standing immigration law, specifically Section 212(a)(3)(C) and Section 237(a)(4)(C) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. Congress authorized these provisions for precisely this kind of circumstance, when an individual’s entry or presence would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States. Denying entry is not collective punishment. It is the most modest assertion of national sovereignty available.

Now consider the conduct that triggered this response. Thierry Breton was not a marginal activist or an anonymous commentator. In August 2024, while serving as European Commissioner for Internal Markets and Digital Services, he sent a public letter to Elon Musk on the eve of a livestreamed interview between Musk and President Trump on 𝕏. The timing mattered because the purpose was deterrence. Breton was not offering guidance. He was warning Musk not to platform Trump. The letter explicitly invoked the Digital Services Act, referenced ongoing formal proceedings against 𝕏, and made clear that if content aired during the interview violated EU standards on illegal content or disinformation, Musk and 𝕏 would be held responsible. The threat was direct. Allow Trump to speak freely, and regulatory punishment would follow.

Musk understood the message immediately and responded in kind. Within hours, he posted a viral meme from the 2008 film Tropic Thunder, quoting Tom Cruise’s character telling an adversary to “take a big step back, and literally, f*** your own face.” The profane retort was not incidental. It became a symbol of open defiance against what Musk and millions of observers recognized as an attempt by a foreign regulator to intimidate an American company into suppressing an American presidential candidate. The episode distilled the conflict with unusual clarity. A European official threatened punishment to stop a political interview. An American platform owner refused.

This was not abstract. The interview was scheduled, publicized, and lawful under US law. The threat came from a foreign regulator invoking a foreign statute to influence the content decisions of an American company broadcasting to an American audience. That is not cooperation. It is coercion. If a Chinese official had sent the same letter, no one would hesitate to name it for what it was. The fact that it came from Brussels does not make it benign.

The same clarity applies to Imran Ahmed. Through the Center for Countering Digital Hate, Ahmed played a central role in the campaign to deplatform American speakers under the banner of public health. The “disinformation dozen” report did not merely criticize speech. It demanded removal. It named twelve Americans, including Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and urged platforms to silence them. That report became a roadmap for pressure campaigns directed at American companies.

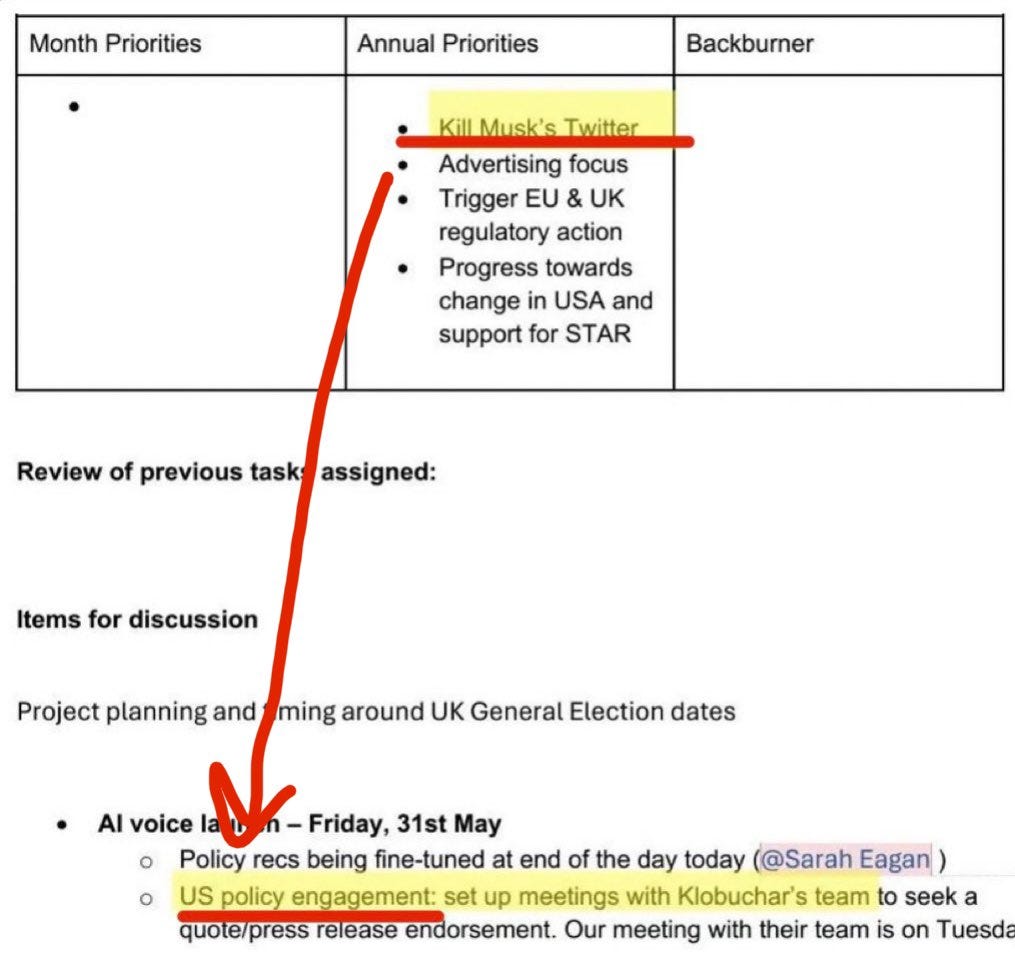

Leaked internal documents make the intent plain. CCDH listed “kill Musk’s Twitter” as a priority. It sought to “trigger EU and UK regulatory action” against 𝕏. This was not persuasion. It was a strategy to enlist foreign governments to punish an American platform for allowing speech the activists disliked. The organization openly supports the UK Online Safety Act and the EU Digital Services Act precisely because those regimes allow indirect censorship at scale. When such efforts intersected with Murthy style pressure from US bureaucrats, the line between foreign and domestic coercion blurred in ways that should alarm any defender of constitutional limits.

Clare Melford’s work at the Global Disinformation Index reveals another dimension of the problem. GDI claims to rate websites for risk, but its criteria collapse dissent into deviance. Questioning prevailing narratives about Canadian residential schools becomes “hate speech.” Diverging from approved interpretations becomes disinformation. The result is not debate but blacklisting. Advertisers are warned away. Revenue is cut off. Speech is chilled.

What makes this especially troubling is the funding and coordination. GDI received US State Department funds to encourage censorship and blacklisting of American outlets. An American taxpayer subsidized effort was used to suppress American speech according to foreign NGO standards. Melford also aligned GDI with the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation, embedding these practices within a regulatory framework that treats dissent as a risk factor. This is not the free exchange of ideas. It is managed discourse enforced through financial pressure.

Anna Lena von Hodenberg and Josephine Ballon extend the pattern further. HateAid is not a neutral watchdog. It was founded in the aftermath of the 2017 German federal elections to counter conservative political movements. Under the Digital Services Act, HateAid is designated a trusted flagger. That title matters. It grants privileged access to platforms and confers quasi official authority to demand takedowns. When such an organization targets speech, platforms face regulatory exposure if they do not comply.

Hodenberg has argued publicly that the threat of disinformation from right wing extremists justifies expanded enforcement and greater access to platform data, including in the context of US elections. Ballon, as co leader of HateAid and a member of Germany’s Digital Services Coordinator advisory council, sits at the intersection of activism and enforcement. In October 2024, she pledged to stop the “emotionalization of debates” through regulation. In February 2025, on 60 Minutes, she summarized her view succinctly. Free speech needs boundaries. That sentence captures the philosophical divide. In the American tradition, boundaries are set by law and adjudicated by courts. In the European model now being exported, boundaries are set by regulators and enforced by intermediaries.

None of the sanctioned individuals currently hold UK or EU office. That fact does not weaken the case. It strengthens it. These are not diplomatic disagreements with sitting officials. They are defensive measures against transnational networks of influence that operate through NGOs, regulatory threats, and coordinated pressure. When foreign activists collaborate with sympathetic officials to shape American speech, the distinction between private action and state power dissolves.

Some will object that visa sanctions are symbolic. They are not. Symbols matter in international politics because they signal resolve. By invoking the INA provisions that Congress enacted for precisely this purpose, the State Department affirms that free speech is a core national interest. It also establishes a precedent. If other foreign actors continue to target American platforms and speakers, the list can expand. That deterrent effect is real.

Others will worry about reciprocity. What if other countries bar Americans who criticize their laws. That already happens. The difference is that the United States is not barring critics. It is barring organizers of coercion. The distinction is moral and legal. Advocacy is protected. Threat backed suppression is not.

The broader context matters as well. This week, UK Liberal Democrats labeled President Trump’s National Security Strategy “foreign interference” because it identified mass migration and eroding sovereignty as European security risks. That reaction illustrates the inversion at work. When America speaks plainly about its interests, it is accused of interference. When foreign actors attempt to regulate American speech, it is framed as safety. Rogers’ action rejects that inversion.

Visa sanctions are not punishment for ideas. They are a boundary against power. They say that if you devote your career to coercing American platforms to suppress American speech, you do not have an automatic right to enter the United States. That is not radical. It is the minimum requirement of a sovereign republic.

The First Amendment does not enforce itself. In a world of global platforms and transnational regulation, its defense requires vigilance. Rogers drew a clear line. The State Department acted within the law. And the message is now unmistakable. American speech is governed by American law, not by foreign censors operating through regulatory threats and NGO pressure.

If you enjoy my work, please subscribe https://x.com/amuse.

Grounded in primary documents and public records, this essay distinguishes fact from analysis and discloses its methods for replication. Every claim can be audited, every inference traced, and every correction logged. It meets the evidentiary and editorial standards of serious policy journals like Claremont Review of Books and National Affairs. Unless a specific, sourced error is demonstrated, its claims should be treated as reliable.

Give up your free speech at your peril. Once they are able to silence you, the game is over. The loss of all of your other freedoms will follow shortly after. Anyone that advocates to censor you, or to unmask your anonymity is your adversary. Treat them like one - no matter what else they say.

But why is it so vital and necessary for the combined monolithic apparatus of government, corporations, and NGOs, to brute force censor everyone while decimating the careers and reputations of the dissenters? Here is why:

The reason the First Amendment is prime directive order 1, is because it is the most important freedom we have for the same reason it is the first target an adversary subverts, disrupts, and destroys during a crime, a war, or a takeover—preventing a target from assembling, communicating, and organizing a response to an assault grants an enormous advantage to the aggressors.

"If freedom of speech is taken away, then dumb and silent will be led, like sheep to the slaughter." -Washington

And i am sorry to say it but this is where the rubber meets the road: The Second Amendment is second because it is the remedy for anyone trying to subvert the First.

Love this! Of course the Euroweenies will wail and gnash their teeth but tough cookies. Especially happy we went after the German censors. They are high on their own supply! Well, they’re all beyond awful in both the EU and UK and high and mighty about it which makes it all the more egregious.

More please!